- Executive Summary

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1.0 Parking and the Home

- 2.0 The Kent Data

- 3.0 Resident Views

- 4.0 Case Studies

- 5.0 Conclusions & Recommendations

- Bibliography

Sign in

1.0 Parking and the Home

The history of housing design in the 20th century is also a history of our relationship with love for – and fear of – the car. Virtually no one owned a car at the start of the century. It was the preserve of the rich and certainly of no consequence in the design of housing. The roads in housing schemes were there to accommodate delivery vehicles, bin trucks, ice cream vans and hearses, most of which were horse drawn.

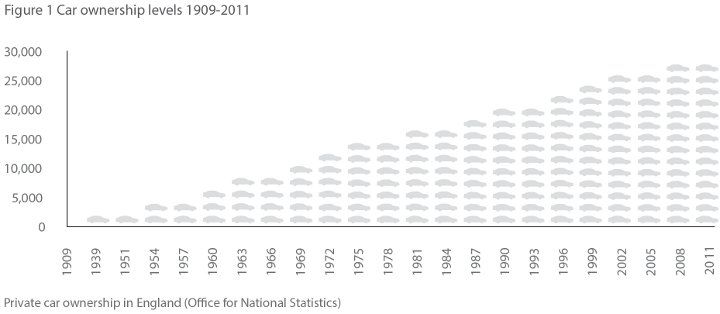

Figure 1 - Car ownership levels 1909-2011

Figure 1 - Car ownership levels 1909-2011The explosion of housebuilding in the 1920s, which saw the sprawl of ‘Metroland’ into the countryside around cities was initially also largely unconcerned with the car. The impetus was the expansion of public transport, trams, buses (and the Tube in London) which created development value within walking distance of the bus stops and stations. The ice cream vans and hearses may now have been petrol powered but in all but the most affluent suburbs they had little competition from cars.

However just as mass suburbia was taking off in the UK the era of mass car ownership was dawning in the US. The mass production of the Model T Ford in the US and a little later the Austin 7 in the UK made car ownership available to the middle classes. Housing brochures from the 1930s start to show driveways and garages for the display of this new consumer leisure item. However for most it remained just that, a leisure toy, for holidays and day trips. Public transport remained the preferred means of commuting to work while shopping was done on foot in the local high street.

After the war the levels of car ownership were still tiny compared to today’s figures. Private car ownership was not much more than 5 Million vehicles by 1960 compared to 27.3 million today, while the total number of vehicles on the road (including commercial vehicles) rose from just under 9 Million in 1961 to 34.5 Million in 2012. The rise in car ownership over that period has averaged 3% a year, dropping to 0.5% in times of recessions but always bouncing back. It is not at all clear that all of the policy measures to reduce car use in the last 10 years have had any perceivable effect on this rate of increase.

This rise in car ownership was predicted, with remarkably accuracy, in 1963 by Sir Colin Buchanan in his report Traffic in Towns1 for the Ministry of Transport. He wasn’t far off in suggesting that car ownership would quadruple to 40 Million vehicles by 2010. His report draws the following conclusion from these figures:

‘It is impossible to spend any time on the study of the future of traffic in towns without at once being appalled by the magnitude of the emergency that is coming upon us. We are nourishing at immense cost a monster of great potential destructiveness, and yet we love him dearly. To refuse to accept the challenge it presents would be an act of defeatism’.

He predicted that the day was coming when people would take a car ‘as much for granted as an overcoat’ and suggested that there were only two options open to us; to restrict the use of the car, or to entirely redesign our towns and cities to avoid them becoming clogged with congestion. In a quote that could apply to some of the housing estates covered in this research the report states that inaction will mean that ‘either the utility of vehicles in town will decline rapidly, or the pleasantness and safety of surroundings will deteriorate catastrophically – in all probability both will happen’.

Buchanan made a complex series of recommendations balancing restrictions on the car with measures to accommodate the growth in traffic that was seen to be inevitable. The former were however largely forgotten and policy-makers focussed on Buchanan’s suggestion that towns and cities should rebuild themselves with modern traffic in mind.

Buchanan was not directly concerned with residential development. However the dire warnings of growing car ownership were also troubling residential planners. The high-density council housing estates of the era, inspired by the writings of Corbusier and the Bauhaus, sought to apply similar solutions to those suggested by Buchanan. Parking was in basements and undercrofts while pedestrian streets were in the sky, safe from the ever-increasing traffic.

In the suburbs and new towns it was also seen as vital to separate cars and pedestrians. The model for this was Radburn, a housing estate in New Jersey designed by Clarence Stien and Henry Wright in 1929. This was the ‘Garden City’ redesigned for the motor age, with a vehicle route at the front of the house and a pedestrian route to the rear, the idea being that pedestrians could move around without coming into contact with cars.

So popular did this model become that Radburn layouts became the norm for most low-rise social housing and new towns in the UK from the early 1960s until as late as 1980. It was taught in architecture and planning schools as the correct way to do things, although in a change from the original, houses were supposed to face onto the pedestrian route and back onto the car route and parking bay.

Private builders were much less keen on Radburn layouts. House builders were interested in ‘kerb’ appeal so that their houses needed to face onto the street, preferably with a driveway and garage where the family car could be displayed and, of course, washed at the weekend. The developers of private estates were however equally keen to avoid through-traffic and to create quiet, safe environments, hence the attraction of the cul-de-sac. The fundamentals of this type of residential layout were codified in 1977 with the first publication of Design Bulletin 32 (DB32)2 by the Department of Transport. This was based on the idea of a hierarchy of ‘Distributor’ streets; Primary, District and Local, leading to ‘Residential Roads’ serving the dwelling. Restrictions on frontage access to distributor roads and the avoidance of through traffic on residential roads created the dendritic cul-de-sac structure of many housing schemes of the era.

What is common to these schemes from the 1960s through to the early 1990s is an acceptance that car ownership would continue to rise and that this was not a particularly bad thing. The main job of policy makers was to cater for the safe and efficient movement and the adequate parking of this increasing number of cars. DB32 leaves parking standards to be set by each local authority based on local circumstances. However it does give guidance suggesting that ‘few drivers are prepared to use parking spaces more than a few metres from their destination’.

While it accepted that unallocated communal provision would mean that the total amount of parking only needed to match the projected number of cars, it suggested that parking should ideally be within the dwelling curtilage. It conceded however that, if all spaces are allocated, ‘the number of spaces provided within each curtilage would need to match the maximum number of cars that the different sizes and types of household that would be likely to occupy the dwelling would be likely to own’. Based on this, some authorities set parking standards as high as 400% for larger houses and 2-300% became the norm in suburban areas. The result of these policies tended to be low-density, car-dominated housing layouts that were widely criticised as lacking in character and impossible to serve with public transport.

The late 1990s saw a significant change in government policy towards housing. The incoming Labour government signalled a major policy initiative in a statement to Parliament in February 1998 by the Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott3 . This was to become known as the Urban Renaissance and included setting up the Urban Task Force Chaired by Richard Rogers (Lord Rogers of Riverside) which reported in 19994 , followed by an Urban White Paper in 20005 and the establishment of the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) with a remit to improve the quality of design.

As part of this new approach, planning policy was updated. Planning Policy Guidance Note 3 on Housing6 had originally been published in 1992 but was updated in March 2000 to include policies on; the proportion of housing to be built on brownfield land, increasing housing densities and improving design. It also recast the standards for parking provision, suggesting that parking standards, especially for off-street car parking impact significantly on housing density and the amount of land required for new housing. It stated that ‘car parking standards for housing have become increasingly demanding and have been applied too rigidly, often as minimum standards. Developers should not be required to provide more car parking than they or potential occupiers might want’.

The policy instructed local authorities to revise their parking standards to allow for ‘significantly lower levels of off-street parking provision’. It went on to say that ‘Car parking standards that result, on average, in development with more than 1.5 off-street car parking spaces per dwelling are unlikely to reflect the Government’s emphasis on securing sustainable residential environments’. This represented a reversal in policy. Instead of minimum standards catering for the worst-case scenario, planning authorities were told to set maximum standards regardless of anticipated car ownership. The reasons were partly the efficient use of land, but also a belief that a reduction in parking would support wider government policy to reduce car use.

This wider government policy was articulated in The Transport Act 2000 and its planning policy equivalent PPG13 (Transport) first published in March 20017 . This set out a range of land-use policies to reduce car use and promote public transport. This included policies to concentrate new house-building in existing towns and cities or new settlements likely to reach a population of 10,000 within ten years. PPG 13 echoed the parking policies in PPG 3 stating that: ‘Standards should be designed to be used as part of a package of measures to promote sustainable transport choices and the efficient use of land’. The implication being that an overprovision of car parking within new housing schemes will encourage car use and undermine public transport.

Alongside this change in policy there was a move to address the design of residential areas with regard to the car. In 1997, Alan Baxter Associates were commissioned to rewrite DB32 to create a design guide for housing areas that were less car dominated. This was a fraught exercise because of the issue of liability – highways engineers who followed DB32 couldn’t be held liable for any traffic accidents. Eventually it was agreed that Baxter’s report, published in 1998 as ‘Places Streets and Movement’ 8 would be a ‘guide’ to the implementation of DB32 rather than its replacement. The report did nevertheless recast much of the guidance on the design of residential roads and had a major influence on many of the case studies in this report.

On parking the report states:

‘Where and how cars are parked is critical to the quality of housing areas, new or old. The location of parking is something which can arouse immensely strong feelings. A very careful balance has to be struck between the expectations of car owners, in particular the desire to park as near their houses as possible, and the need to maintain the character of the overall setting’.

The report suggests that parking can be included in layouts in three ways: parking courts to the rear of property, provided that they are overlooked, in-curtilage parking either down the side or at the front of the house, provided that it doesn’t ‘break up the street frontage’ and on street parking. Rather optimistically they suggest that ‘In curtilage parking spaces can be grassed over if not needed’. The reality in our case studies is that gardens are more likely to be pressed into service as a second car parking space.

DB32 was eventually replaced with the publication of ‘Manual for Streets’ in March 2007 9. This was developed by a team led by WSP and finally grasped the nettle by creating guidance that, if followed, would absolve highways engineers of liability. The section on parking starts with a statement –that in new housing estates ‘the availability of car parking is a major determinant of travel mode’.

However it also recognises the potential adverse consequences of under provision of parking:

‘Local planning authorities will need to consider carefully what is an appropriate level of car parking provision. In particular, under-provision may be unattractive to some potential occupiers and could, over time, result in the conversion of front gardens to parking areas. This can cause significant loss of visual quality and increase rainwater run-off, which works against the need to combat climate change’.

The guidance draws heavily on the main previous piece of research on parking ‘Parking – What Works Where’ by English Partnerships and Design for Homes published the previous year 10. This draws on work by Alan Young and Phil Jones on the 1991 census to show that the average household level of car ownership was 1.1 for a house with 5 habitable rooms. If all parking spaces were unallocated a row of ten houses would require 11 parking spaces (as pointed out in the original version of DB32). However if each house were given an allocated parking space, inefficiency would be introduced into the process. 19% of houses wouldn’t have a car and so their space would be empty while some would have two cars. They calculated that in this case the ten houses would need 13 spaces to accommodate the same number of cars (an 18% inefficiency). Further more in the unallocated scenario the spaces would double up as visitor parking, while in the allocated scenario a further 2 spaces (15 in total) would be required. ‘Manual for Streets’ picks up on this and while it does not suggest a level for in-curtilage parking, it suggests that a significant amount of unallocated, on-street parking be provided in preference to in-curtilage parking.

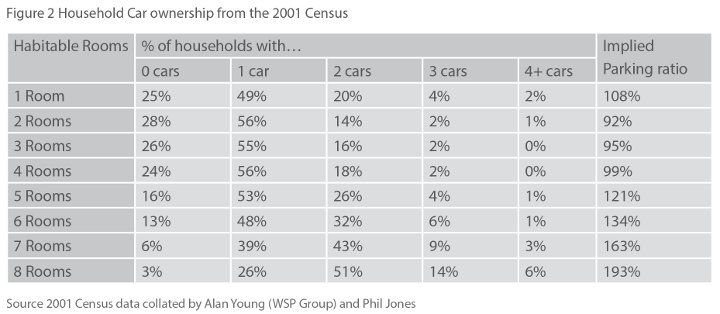

The What Works Where research includes data from Alan Young and Phil Jones based on the 2001 Census that calculates the level of car ownership in different types of housing by tenure, size and type. The headlines are that the main factor affecting car ownership is the size of the house, a house with 8 habitable rooms typically has twice as many cars as a 4 room house. Owner-occupiers have 0.5 more cars than social tenants in all house sizes and types, but flats only have marginally fewer cars (0.1-0.2) than the equivalent sized house. The following table is calculated from the figures in this report.

The final chapter of this story relates to the current coalition government and its stated intention to “end the war on motorists” 11. In doing this they removed the national policy limits on Parking in PPG/PPS 3. The National Planning Policy Framework published on March 201212 states that parking standards should be set by local planning authorities with reference to the accessibility of the development and the availability of public transport, the size and type of the property and local levels of car ownership. As quoted in the CIHT guidance note on parking13 , the government’s view is that ‘significant levels of on-street parking had caused congestion and danger to pedestrians’ and urged local authorities ‘to make the right decisions for the benefit of their communities’. The clear implications being that the right decision would be an end to unrealistic restrictions of people’s right to park their car.

Figure 2 - Household car ownership from the 2001 census

Figure 2 - Household car ownership from the 2001 censusThe issue of car ownership, use and parking has been an important part of housing design for more than 50 years, yet the area remains remarkably under researched. For the first thirty of these years the emphasis was on accommodating the growing levels of car ownership and for the second twenty the focus shifted to reducing car use. The third phase is just beginning with the removal of national restrictions on residential parking provision. Given that this happened so recently there has been no time for it to filter down into local planning policy and the impact is therefore unclear. It could however herald a return to the low-density car-dominated housing estates of the 1980s. Alternatively it might lead to a reassessment of the way that the car is accommodated in housing development in a way that recognises likely levels of car ownership without undermining the quality of the place.

No Parking

Throughout much of this period the policy has been based on the assumption that reducing the level of car parking reduces car use. However there is remarkably little research to back this up. One of the few pieces of work that found a positive correlation between the amount of parking provided and the level of car use was a Transport for London research report published in 201214 . Like the ‘What Works Where’ report it identified correlations between household size, tenure and car use. However the research also found correlations between parking provision and car ownership, and between car use and the home’s PTAL Rating (Public Transport Accessibility Level). Given that planning policy in London also links the allowable level of parking to the PTAL Rating, cause and effect becomes unclear. However it does suggest that the situation in urban locations may be different. Other than this research is very limited. The CIHT even state in their 2012 guidance note that there is ‘no clear evidence to show that access to existing and/or proposed public transport measures and the distance from key facilities, including the quality of the walking and cycling infrastructure that provides the links, affects car ownership’.

No Parking

Throughout much of this period the policy has been based on the assumption that reducing the level of car parking reduces car use. However there is remarkably little research to back this up. One of the few pieces of work that found a positive correlation between the amount of parking provided and the level of car use was a Transport for London research report published in 201214 . Like the ‘What Works Where’ report it identified correlations between household size, tenure and car use. However the research also found correlations between parking provision and car ownership, and between car use and the home’s PTAL Rating (Public Transport Accessibility Level). Given that planning policy in London also links the allowable level of parking to the PTAL Rating, cause and effect becomes unclear. However it does suggest that the situation in urban locations may be different. Other than this research is very limited. The CIHT even state in their 2012 guidance note that there is ‘no clear evidence to show that access to existing and/or proposed public transport measures and the distance from key facilities, including the quality of the walking and cycling infrastructure that provides the links, affects car ownership’.

The remainder of this report explores these issues in more detail in relation to Kent. Chapter 2 analyses a data set collected on 402 recent developments in Kent comparing parking provision, car ownership and customer satisfaction. Chapter 3 looks in more detail at six case studies drawn from this list to look at the reality on the ground of parking provision and actual parking patterns. Chapter 4 details findings from a survey and focus groups with the residents of these estates. This allows us to draw a series of conclusions in Chapter 5.

1 Colin Buchanan, Traffic in Towns Report (1963)

2 DoE, Design Bulletin 32 (May 1992)

3 Prescott statement to Parliament (February 1998)

4 Urban Task Force, Towards a Strong Urban Renaissance (1999)

5 ODPM, Our Towns and Cities - the Future - Urban White Paper (2000)

6 DCLG, Planning Policy Guidance 3: Housing [England and Wales] (2000)

7 DCLG, PPG 13: Transport [England and Wales] (2001)

8 DETR, Places Streets and Movement (1998)

9 DfT, Manual for Streets (2007)

10 English Partnerships, Car Parking: What works where (May 2006)

11 Philip Hammond, Announcement at the DfT, May 2010

12 Announcement reported on CLG website and corresponding CLG letters to Chief Planning Officers (14 January 2011) and Clive Betts MP (3 January 2011)

13 CIHT, Guidance Note - Residential Parking, 2012

14 Transport for London, Residential Parking Provision in New Developments (2012)